💡 EDIT 2021/03/04, This post was a collaborative effort between Geoffrey Teale and myself, originally published post on Inside Heetch.

Introduction

In this article, we’ll talk about our experiences scaling up our development team at Heetch. In particular, we’ll focus on the organisational issues that emerged from growth, and from technical changes. Finally, we’ll introduce the concept of “Developer Care”, and how we’ve used it to overcome these challenges.

A little history

In the early days of Heetch, life was simple. We had a monolithic web application developed in Ruby on Rails and a small team of pioneers. At this point communication was easy. Everyone knew who was working on what. Ideas were freely shared. Consensus on how, when and why to do things was found.

As Heetch’s user base grew we started to experience technical challenges. Dealing with the increased load on the application was becoming difficult. We had to handle location data for thousands of drivers in real time.

We began to struggle to integrate the competing requirements of different aspects of the business into a single application. It was in this context that we made a decision to shift to a micro-service architecture, utilising Docker, and written in Go. Later we added further services in Elixir.

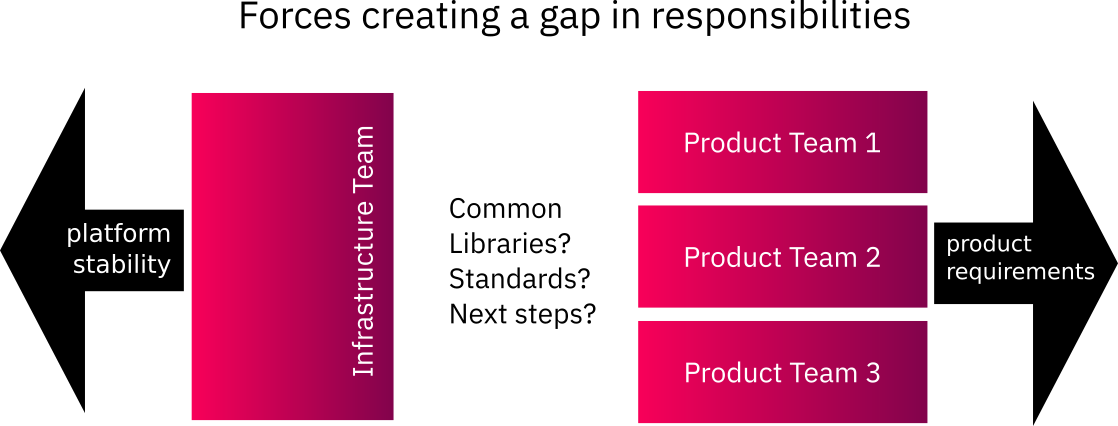

In line with this new technical architecture, our development team split into product-area specific teams. Each team looks after its own list of requirements. Each team has its own collection of micro-services. A separate infrastructure team provides a common platform to run the micro-services in.

A problem solved, a problem found

Heetch’s micro-service architecture and the associated business-area aligned team structure have been in place for some time now. The teams have succeeded in working, and growing with a tight focus on the business requirements and are free from the complexity of competing demands on the same application logic and data structure.

Despite these successes, we have seen a new issue arise in their wake.

Distance between teams

Although each individual team retains the ease of communication that existed in the pioneer team, cross-team communication is much harder to manage. This is a common problem in large or growing companies, but we noticed there was a specific impact on our technical output.

The common context and shared ideas are no longer a natural outcome of interactions across the whole engineering team — it simply isn’t possible to hold informal conversations on that scale. Each team is less aware of the problems and solutions found by the others.

As each team faces a new technical challenge, they find their own way to solve it. There is no lack of skill in the teams, but the priorities of each team are bound to business requirements, as are the deadlines. This means that the design of fundamental architecture, and tooling around the projects, has to be completed as a side effect of product work.

Justifying time to maintain and improve those solutions is a challenge in that context, and is a source of frustration to some engineers.

Drag and Technical Debt

The slow build up of bespoke solutions for each team creates a drag factor across the entire company. Each team pays a price for this in terms of its own agility, and tech debt can arise when maintenance work is not a clear priority.

The entire organisation pays a price in terms of duplicated effort, and missed opportunities to benefit from good ideas that arise in one team. Though senior managers can sometimes see these opportunities, the existing structure of teams doesn’t lend itself to assigning resources to work on cross-team projects, and such efforts may compound the problem of work duplication if multiple teams have already found or built solutions.

The lack of a clear owner for these problems

The shared infrastructure team in the new organisation was originally intended to take ownership of some of the issues described above and promote solutions for them. However, the business of providing fundamental cloud services and infrastructure has always been a more pressing concern.

The skills required to support such infrastructure don’t always overlap with those needed to build and maintain libraries and tooling. In this way, the same strains are felt in the infrastructure team as in the product teams when attempting to solve these kinds of problems.

Google, famously, developed their Site Reliability Engineer role in response to the divergence of priorities and skills between ops engineers and developers. Many companies also see it as the role of DevOps to put software development and production requirements into the same context (and share the scope and priorities).

The issue we faced was somewhat different. Our engineering teams are comfortable with the production platforms and tooling, provided by our Infrastructure team. We didn’t need to bridge each development team to the production environment, but rather find ways to develop on that platform efficiently across multiple teams and a multitude of services.

We identified the following areas of common concern between teams that lacked someone to own and address them company wide:

- tooling and standards for metrics, monitoring, caching and logging

- common patterns for inter-service communication

- establishing idioms and good practice

- migration from one technology to another

- reduction of boilerplate code

- simplification of back-end tool and infrastructure usage

- eradicating duplication of effort by providing common solutions

- solving other common technical concerns such as efficient storage and performance improvements

A plan to fill the gap

We decided to build a new kind of development team to fill this gap in our organisation.

This new team is separate from the product teams. It is not bound to the requirements or priorities of any one business area, but strives to serve the developers who are.

We don’t focus on the question “What should this application do to better serve the business and its customers?”, but rather “How should this application be structured to make it easier for product developers to do their jobs?”.

This is a broader scope from a business point of view, but a far narrower scope from a technical point of view.

By listening to every product team’s needs, we see the common pain points. We can predict where the same problems are likely to occur in other teams.

By owning the fundamental libraries and tooling we have filled the gap in responsibility we saw opening up. Maintaining and improving these solutions is our priority.

To clarify these ideas, we set out, now, the following manifesto for this new team we dubbed “Developer Care”:

Developer Care Manifesto

Know Our Mission

- Don’t look after cloud infrastructure. It requires a different set of skills and has a different relationship to product priorities.

- Don’t create or maintain “Business Logic”, keep a clear line of demarcation.

- Do create tools and libraries that shield product engineers from infrastructure concerns.

- Do talk to people. Listen to their pain points. Keep track of those pain points, even when they’re ephemeral.

- Do stay up to date, and don’t lose track of where the industry is going.

- Do anticipate tomorrow’s needs, and arrive with the right tools at hand.

- Do follow Open Source methodologies, even when we’re not doing open source. Publish as much code as possible. Assume that somebody else is going to read what you write.

Act on the right time-scale

- Do respond to pressing needs. Sometimes a bandage is appropriate.

- Don’t over commit to “changing bandages”. Plan for surgery.

- Do look for the issues ahead of us, and try to create “tech credit” instead of just fighting “tech debt”.

- Don’t be bound by the release schedule of product teams.

- Don’t waste other teams time. Deliver when the product is ready. Remember, “less haste, more speed”.

What kind of people are we?

What kind of people are we?

- We are engineers who serve engineers. We don’t communicate via a non-technical manager.

- We are people who care about the code, and about the engineers who’ll use it.

- We are humble.

- We know the difference between complexity and complication. We embrace the first and reject the second.

- We practice safe coding. We release our code to others with extensive test coverage and detailed documentation.

- We are good listeners.

- We are excellent communicators. We explain what we’re doing, and why we’re doing it. We explain before we’re asked to explain.

Building the team

The new team began with two engineers, but soon it became clear that we would need to recruit. The “people” section of the manifesto sets out a very specific set of qualities. They aren’t purely about technical ability, but about character and personality type.

We need people who feel inspired to help other developers. Finding such people could be difficult. By crafting the job specification to convey the intent of the team, we’ve managed to be successful in reaching the right people. We’re building a team of people who see what we do as a labour of love.

Our candidates are often motivated to apply without previous exposure to Heetch. People who understand are intent are attracted by the nature of the role, and the attitude it conveys.

We have the luxury of being a 100% remote team. It broadens our catchment area to anyone living in the main European time zones. We believe this is a crucial factor in successful recruitment.

Building the Developer Care team has had an impact on the other roles we hire for too. By taking away drag-factors we make those roles clearer and more attractive. Examples of our jobs specs for a broad range of roles, including developer care can be found here: https://www.heetch.com/jobs/

Measuring effectiveness

It can be daunting to measure the effectiveness of team with goals that are so abstract from what is delivered to our end-users. Our success is defined by a reduction in problems faced and by the resulting positive experience of other development teams.

Testing for the absence of a problem is harder than testing for a positive indicator. There are still a few key points we watch out for.

What should we see with the Developer Care team in place, and functioning well?

Product teams should:

- be moving faster.

- face challenges related to the day-to-day business of Heetch rather than with low-level architecture or environmental concerns.

- not be duplicating effort on disparate solutions.

- experience fewer technical blockers.

- be proactive in reporting problems to the Developer Care team.

The Developer Care team should:

- see requests coming in to fix issues for which we already have solutions.

- have a clear list of requirements resulting from interaction with the product teams.

- have “tech credit” projects that will be ready to move the organisation forward when the need arises.

Though some of these factors are not always easy to discern, we can attempt to gather data on them. Talking to the product teams and collecting feedback in retrospectives, and surveys can help. We pay attention to what comments developers make in their daily work.

Conclusion

So far, we’ve been pretty happy with the team we created. We’ve found that product teams focus on the product priorities as much as they like and we’re able to introduce changes in a smoother way.

We share a lot of what we produce under Heetch’s organisation on github.com (“Developer Care” work is tagged “team-boost”). We’d like to share some of our ideas too. We’re now looking to expand our developer care team and to talk to over companies about their experiences to see if we can make further improvements.

Do you have a micro-service architecture, but still find it hard to deal with tech debt? Do your developers feel constrained by pressing product or infrastructure needs? Do you feel that your teams are grinding to a halt? You may be in the need of a “Developer Care” team.

If you do try to build a team like this, we’d love to hear about from you and to exchange about our experiences.